Without doubt, the ethnic group which has gained the

most from railroading have been black males. Black people have labored in

the railroad industry from the very beginning - slaves, at first - laying

the original rails in Maryland in the 1830s.

Without doubt, the ethnic group which has gained the

most from railroading have been black males. Black people have labored in

the railroad industry from the very beginning - slaves, at first - laying

the original rails in Maryland in the 1830s.Content provided by Those Classic Trains

Without doubt, the ethnic group which has gained the

most from railroading have been black males. Black people have labored in

the railroad industry from the very beginning - slaves, at first - laying

the original rails in Maryland in the 1830s.

Without doubt, the ethnic group which has gained the

most from railroading have been black males. Black people have labored in

the railroad industry from the very beginning - slaves, at first - laying

the original rails in Maryland in the 1830s.

Black people have made many significant - largely unnoticed - contributions to the industry. Among the roll of these unsung geniuses are Elijah J. McCoy (the Real McCoy automatic lubricator), Granville T. Woods (telegraph equipment) and Andrew J. Beard (the Jenny coupler - first successful automatic coupler used exclusively on passenger equipment in the Varnish days).

However, the best known image of the black railroader, and indeed of passenger service in general, is the Pullman Porter: known universally as "George" in honor of Mr. Pullman. The origin of the black Porter is an illuminating look at late 19th Century America.

Shortly after the Civil War, when George Pullman's empire was starting to blossom, there were several sleeping car operators. Pullman was by no means the largest. In this free-for-all competitive environment, the more amenities one could offer, the better one's trade position. This led, among other things, to the over-decorated "Varnish" equipment, Parlor service, club and lounge-obs cars, and the fierce dining car competition.

It happened, just then, that a great many former slaves who had been

liberated during the Civil War were both a major labor resource and something

of a social problem (there being so many of them and no one having any real

notion of what to DO with them, now that they were free).

It happened, just then, that a great many former slaves who had been

liberated during the Civil War were both a major labor resource and something

of a social problem (there being so many of them and no one having any real

notion of what to DO with them, now that they were free).

In Pullman's quest for an ever better competitive edge, the idea of providing a personal servant to each car's passengers seemed like a practical marketing ploy. So several dozen of these "colored" men, who had been house servants in the Antebellum South were installed as servants to the passengers and general custodians of their assigned car.

The idea was a resounding success. The concept of a personal servant fit in well with the overblown Victorian opulence of the equipment and with the social status of the passengers. Moreover, the black house servant was a deeply ingrained image in the American psyche- a symbol of a gracious, almost mythical, way of life that had vanished within living memory.

In this role, the former house slaves found a social acceptance denied to virtually all other blacks in America (not to mention Jews, Irish, Orientals, Catholics, Germans, Poles, even English - 19th century America was not, by any stretch of the imagination, the melting pot it is portrayed as being).

This is not to say that the black Porters achieved any degree of social equality: black is black, servants are servants. However, the relationship between passenger and Porter created a rigidly defined structure of social status almost identical to the former plantation culture. This allowed two vastly different and mutually antagonistic social groups to interact comfortably.

Strictly speaking, these Porters were not Pullman employees. At first, they were an odd species of sub-contractor: working the cars with Pullman's consent and logistics, but their only compensation being their customer's tips. This was a common practice in many industries, notably transportation, hotels and restaurants- and the origin of the traditional tips to such employees.

The practice was eventually struck down by a Supreme Court decision which ruled that Porters are, in fact, Pullman employees and thus have to be paid. (As a result of this, Porters today receive minimum wage.) But for much of the Golden Age, the traditional tip upon debarking has been a matter of great concern to a poor and socially disadvantaged class.

As late as 1910, 2/3 of all black railroaders were in

the most menial labor categories. A Porter or lounge Steward's spot was

about the best the black man could hope for. This was not helped by their

fellow railroaders - notably the Firemen's and Trainmen's Unions. At Union

insistence, there were "promotable" (white) and "non-promotable"

(black) trainmen; a whole slew of Catch-22 work rules prevented blacks from

acquiring seniority; and even the limited opportunity afforded these "non-promotable"

men were systematically whittled away.

So adamant were the Union efforts that the railroads knuckled under and even the USRA blinked. This injustice was only laid to rest in 1948, when the Supreme Court struck down the Southeastern Carriers Agreement, the then-current labor contract in that part of the country.

It was this lingering racism and the rising hopes of the black railroaders that lead to the first significant Civil Rights action since the Emancipation. In 1925, a black publisher and crusader, one A. Philip Randolph, organized the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters - the first black Union.

This fledgling Union faced a stiff uphill fight at first. Unions generally are unwelcome on railroad property, and a Union of "coloreds" more so. A great many black railroaders were afraid to join a Union because of the risk of losing their jobs and of labor violence (a trait they shared with their white counterparts).

What was worse: in a short 4 years after its founding, the Great Depression hit. Hiring of Porters, and Red Caps ceased between 1930 and 1937, and reduced services resulted in massive layoffs. They hung on, however, and when the Second World War began, membership climbed steadily to reach an all time high of over 12,000 (a great many of these being special hires for troop sleeper service).

*****

The training Porters receive is the most detailed and

exacting: for example, there are no less than 7 paragraphs of detailed instructions

in the Porter's Manual on the proper way to serve a bottle of beer.

The training Porters receive is the most detailed and

exacting: for example, there are no less than 7 paragraphs of detailed instructions

in the Porter's Manual on the proper way to serve a bottle of beer.

The standard of service set by Pullman is finicky: if one of the several dozen pillow cases or towels is taken out and unfolded, it is then "dirty" and cannot be put back again. Supplies such as soap and towels must always be on hand (patrons who have to ask for a bar of soap will not be pleased- albeit they have no other travel option except coach) and the restrooms and upholstery kept spotless.

Porters are on call 24 hours a day for the duration of their trip (plus a couple of hours before and after tending to their car). During the day, they assist their passengers by fetching drinks or snacks, sending telegrams off at the next station, making appointments in the diner, or the barber shop or with the on-train stenographer, and helping to sort through luggage.

In the evening, the Porter has to make down all the berths in his car, quickly laying out the crisp linen sheets and tucking the blankets in with a Boot Camp precision. In the morning, he must just as quickly make them all up again, removing the dirty linens, storing the mattresses, blankets and pillows and folding the sections back into seats.

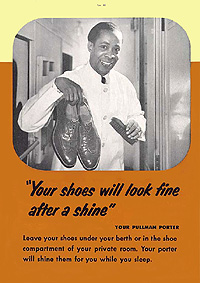

At night, while the passengers sleep, the Porter takes their shoes (which are left by the section, or in a little locker in the wall of the compartment) and shines them to a fine glow. He also watches over the car, tending the heat and air conditioning, always alert to a late night trip to the lavatory which requires the upper berth ladder, and waking the "shorts" who are detraining during the night. (Porters must be circumspect in waking a passenger- never touching them or knocking on the berth too forcefully). If he manages to complete these manifold tasks, he might then arrange with the Porter in the next car to cover him while he grabs an hour or so of sleep.

Discipline among the Porters is maintained by a rigid code of conduct enforced by the Pullman Representative in response to passenger or crew complaints or the reports of anonymous traveling inspectors. Porters may be penalized for tardiness, surliness, inattention, or even for stepping on the lower berth cushion while prepping the upper. Any writeup of this sort is likely to earn the unfortunate Porter a suspension or, if too many demerits mount up, dismissal.

*****

The black Porters have certainly done their duty to

their passengers and to Pullman. One of the most profound examples of the

Porter's devotion is commemorated in the tourist sleeper "Oscar J.

Daniels": the only Pullman car named in honor of a Porter.

The black Porters have certainly done their duty to

their passengers and to Pullman. One of the most profound examples of the

Porter's devotion is commemorated in the tourist sleeper "Oscar J.

Daniels": the only Pullman car named in honor of a Porter.

This car started out as the 16 section Varnish sleeper "Sirocco", which Daniels was assigned to on the Lackawanna railroad. On June 16, 1925, while on a special tourist run, the train derailed on a mud slide.

The cars piled up beside the track with the "Sirocco" lying next to the locomotive, which was leaking steam from a ruptured pipe. A blast of steam came in through the end door, threatening to engulf the passengers. Daniels staggered to his feet, waded through the cloud of steam and fell on the door, forcing it shut.

He was carried, horribly scalded, outside and laid on the ground. There, he refused treatment until his passengers had been looked to and soon died of his burns. In honor of this selfless act, the repaired car was renamed after him.

*****

Today blacks are still predominant in their traditional roles as Porters and Red Caps, although - in an interesting case of reverse desegregation - more whites and latinos are starting to appear. A particular instance of this are the Registered Nurses carried on many streamliners. Black Porters are still the rule in the east and south, although more whites are appearing in the Midwest and a mix of whites and latinos in the southwest.

Black men - and women - are starting to make their way into clerical, technical and middle management positions in ever greater numbers. In something of a milestone, in December, 1968, a New York Central passenger train became the first to operate with an all black crew.

| Baker heater news | rumors and gossip |

| Bearcat | a tough, demanding supervisor |

| Birdcage or Back Porch | open platform observation car |

| Blanket Indian | a Porter sitting on a folding chair guarding his car |

| Brass Hat or Collar | a railroad official |

| Burnt Up | not being tipped by a passenger |

| Candy Run | an easy assignment |

| Con Man | the train Conductor |

| Decorate the platform | to set the boarding stool out and receive passengers |

| Feed Box | dining car |

| Handkerchief Head | an elderly and cantankerous Porter who looks down on younger men |

| Hit The Plush | riding deadhead in coach on a pass |

| Knock-em-off | to brush down a passenger upon detraining |

| Light Housekeepers | passengers who bring their food with them |

| Make Down | to open up a berth and prepare it for sleeping |

| Merry-go-round | being on a rotating assignment or working fill-in assignments |

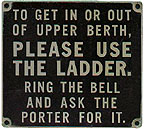

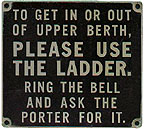

| (the) Midget | the short ladder used to reach upper berths |

| Pension Run | an easy assignment |

| Prince | an easygoing supervisor |

| Rough Rider | a careless or unpleasant Porter |

| Shorts | passengers who get on or off en-route |

| Sign-out Man | supervisor who assigns Porters to various runs |

| Traveling Porter | a Porter who reports another Porter |

| Upstairs and Downstairs | upper and lower berths |

| Walking State Street | on suspension |

| Zebra | a senior Porter with several service stripes |

Go To Part 1: Train Crews & Support Personnel

| Home Site Map Search Contact |

North East Rails © Clint Chamberlin. |